My story, “Halfway Home,” appears in Issue 35 of The Jewish Fiction Journal

My story, “Waiting for the Tumour Board,” appears in Issue 6 of The Quarantine Review.

My story, “Cecilia,” appears on Joyland Magazine.

My story, “Halfway Home,” appears in Issue 35 of The Jewish Fiction Journal

My story, “Waiting for the Tumour Board,” appears in Issue 6 of The Quarantine Review.

My story, “Cecilia,” appears on Joyland Magazine.

Jor liked beginnings of any sort: new beginnings, old beginnings, even in-between beginnings. He was definitely a Cat who liked beginnings. And that was one of the things that set him apart, right from the start, from all the other Cats in The Park.—Chapter One, Humble Beginnings

As you might suspect, The Park’s first leader and the founder of modern zoocracy was my alter ego in that respect. I’ve never liked endings. To me, they hold no promise, despite that silly cliché about one door closing and another opening.

Monday was Jor’s favourite day, as it is mine. Next Monday, I’ll awaken to a different month and a different set of goals, some of which have been on my list for more than three decades. I’m not kidding. One day, a few months ago, I unearthed a list dated 9 August 1987 that scared the heck out of me. It wasn’t that so much of it was never accomplished; it was that so much of it resembled the list I’d made the day before I found it. That 1987 list convinced me that it was time to get on with these things before the final ending took care of them all.

That’s not to say that I’ve done nothing. But when I look at that 1987 list, I see how much of what I wanted to do couldn’t have been done at all in those days. Some fantastic advances in technology had to take place before I could even attempt many of the things on that list, and I feel so lucky to have lived long enough to take advantage of that. That 1987 list was handwritten on lined paper, but so many of my notes for various projects were printed with a dot matrix printer. Before that, I used an IBM Selectric. And before that, I used a manual typewriter. The first word processing software on my first computer was called Volkswriter and it had embedded commands. WYSIWYG was still only a glimmer in the eyes of software engineers.

When I was seventeen, my boss on my second-ever summer job told me that we were all cogs in a wheel. I went home feeling more hopeless than I ever had, even though I knew he was dead wrong. Yes, our reach often does exceed our grasp, but our history—and our story—lies in that reach.

And that’s the reason I decided to use this web site to write about writing The Mammalian Daily. Even though I dislike the idea of writers writing about writing, it’s the history—not the process— that I want to document. I started the story when the world was a different place and the possibilities were by no means endless. I invite you to join me on my journey looking back.

In the meantime, as ever, I have writing to do and people to thank and, in a few days, cookies to eat at the celebration of my one thousandth original article. And, yes, it’s likely there’ll be tears, if for no other reason than that I hate endings.

Just a quick post about elections (or, more correctly, elections vs sortition).

Just a quick post about elections (or, more correctly, elections vs sortition).

One of the fun things about creating a world from scratch, as I did in The Mammalian Daily, is deciding how your characters will live and, in this case, how they will govern themselves.

Since The Mammalian Daily was a political statement in itself, I deliberated for a long time about the best choice of government for the animals who live in The Park. My choice of sortition didn’t just have its origins in my studies of the classical world; it made sense to me, as it did to Aristotle.

The Animals in The Park are still debating the subject and there are many, including director Douglas Cheetah, who are pushing to adopt elections. But I have faith that sortition will stand its ground, at least as long as Sylvana Rana, president of Save Our Political System (SOPS) fights for it.

The Frankfurt Book Fair opens today. Two years ago, I attended it along with Noreen (seen here sporting her Maple Leaf hat), the author of “Lovely To Look At: What Animals Should Know About Humans.”

The Frankfurt Book Fair opens today. Two years ago, I attended it along with Noreen (seen here sporting her Maple Leaf hat), the author of “Lovely To Look At: What Animals Should Know About Humans.”

In the past, large international book fairs such as the Frankfurt Buchmesse and the London Book Fair (and BookExpo Canada, when we were lucky enough to have one here) didn’t encourage writers or other members of the public to attend these professional publishing gatherings. But major changes in the publishing business have forced organizers to acknowledge that remaining a closed shop is not in their best interest.

I was surprised two years ago to see that the Frankfurt Book Fair devoted a day to welcoming the public. And on another day, they welcomed schoolchildren. It makes perfect sense.

In the coming months, I’ll be writing about the experiences I had at the many book fairs at which I displayed The Mammalian Daily. Stay tuned.

Watson the Irish Water Spaniel and Hecuba the hare were the first characters to appear in The Way to Dr. Bourru. But neither Watson nor Hecuba made it into The Mammalian Daily.

Hieronymous, on the other hand, has had a starring rôle, not to mention his own Twitter account. And, just this year, he became the spokesAnimal for GoUnderground, The Park’s oldest hibernation outfitter. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Hieronymous appears about twelve pages into the book, when Watson and Hecuba come upon him outside Dr. Bourru’s office. Hieronymous, who has just come out of hibernation and is a bit confused, hears Watson’s tail wagging and mistakes it for the sound of sympathy. This exasperates Hecuba:

“Honestly, Hieronymous! Sometimes I think you’re still as deaf as the day you were born!”

It seems that from the very beginning, other animals have found Hieronymous exasperating. He’s a bit slow, I admit, but he’s well-intentioned and, to my mind, very sweet and quite vulnerable. But he also has moments of undeniable wisdom. I’d meant him to be just goofy, but he took on a life of his own and I’ve been trying to protect him from himself ever since.

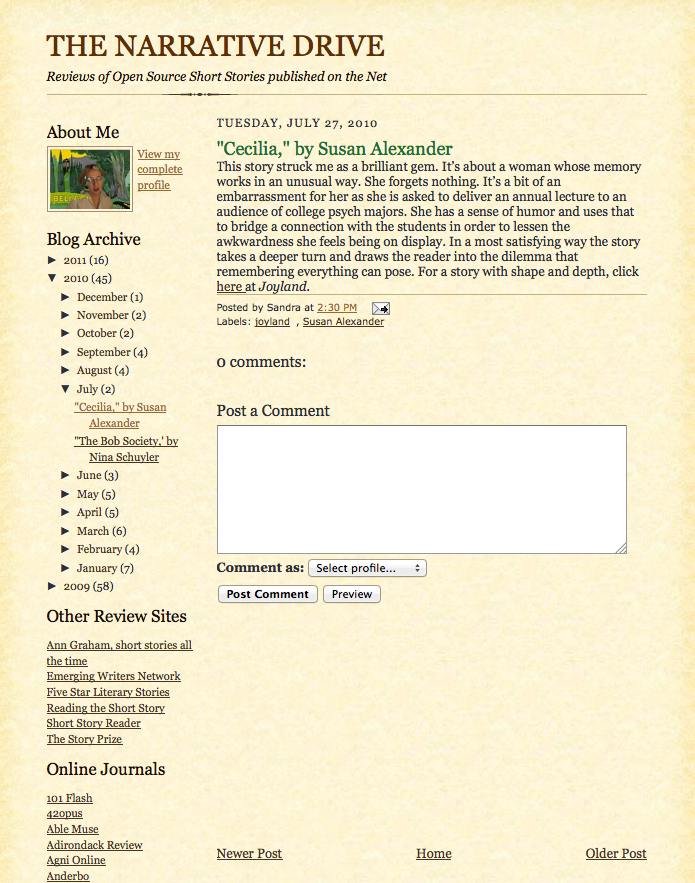

The Narrative Drive: Emory University's Sandra Rouse reviews my short story, "Cecilia," published in Joyland Magazine.

The Narrative Drive: Emory University's Sandra Rouse reviews my short story, "Cecilia," published in Joyland Magazine. The Mammalian Daily: Over two decades of aspiring to help humans see themselves and their follies through satire. Still trying.

The Mammalian Daily: Over two decades of aspiring to help humans see themselves and their follies through satire. Still trying. Agnes and True: Interested in reading great contemporary short fiction? Check out the literary journal that I co-founded.

Agnes and True: Interested in reading great contemporary short fiction? Check out the literary journal that I co-founded.